My favorite chess book

Whenever students ask me what modern chess book I like most, my answer is Willy Hendriks’ book called Move First, Think Later. It is one of the very few chess books of the last 10-15 years that brings something conceptually new, a paradigm shift. It is not a small thing to have the “insolence” to prove that so many ideas deeply rooted in chess literature are mere myths. They keep being taught and passed on to new generations of chess players, usually by people who know very well that it is not how they actually think themselves during the game.

The major theme of the book is that chess is much more concrete than we like to think. Any sort of theoretical concepts, guidelines, rules, evaluations make little sense if they’re not backed up by concrete variations. We would like things to be different. Chess would be so much easier if all we had to do was to memorize a few pages filled with nice chess ideas, and based on that list we could come up with the right moves every time. We learn chess by being exposed to good chess moves, we don’t improve our chess by reading some texts. That is why going over GM games helps so much, and it is how my own chess journey began. We learn by imitation.

Some of his ideas and even entire paragraphs are so close to the way I understand chess, that sometimes I feel that most likely I met Hendriks at some point and he had some kind of revolutionary mind-reading device. It is the book I would have liked to write.

Hendriks may not be right in everything he says, and no doubt his ideas have irritated many, but he presents arguments and examples that are hard to ignore. It is written in an alert, accessible style, has hundreds of well-chosen and thought-provoking examples. I recommend that all serious chess players go through the book, even those who have completely different points of view. I am going to list some of the most interesting ideas, without going into details or concrete examples.

The thought process does not start with a pure static analysis

There is a widespread idea that a serious thought process would begin with some sort of static analysis of the position, trying to understand all strengths and weaknesses. After that, based on those findings, a plan would be formulated, ultimately arriving at a move to serve that plan. It makes perfect sense, but in the real world no serious player does that. From the moment we see the position, almost involuntarily, our mind begins to test different moves, to follow possible scenarios, and it is from the outcome of those scenarios that we realize which positional features are relevant. It is useless, for example, to notice that one particular square is weak, if you have no concrete possibility of getting there. A beautiful lead in development means nothing if there are no concrete ways to open the position and attack. In most cases there are a lot of positional factors that can be “asymmetric”, imbalances are very common. But it is only the concrete analysis of moves that reveals which of them matters. Most of the time, there is no temporal separation of the concrete analysis of the moves and the strategic findings. They run in parallel (as we examine different moves we get a deeper understanding of the characteristics of the position). As Hendriks says, “you can’t have an important positional trait that isn’t connected to an effective move.” When people see the title of the book, their first reaction is something like “What is this guy trying to say, that you just play a move first, and then start thinking? It makes no sense!” Obviously, that is not the meaning of the title. The idea is that you have to analyze (not play!) specific moves first, before you determine what types of chess thoughts make sense.

Verbal protocols do not help

A widespread myth is that one could arrive at the correct move by following some verbal protocol, some general rules that can be learned from textbooks. For example, if the opponent attacks you on the flank, react with a counterattack in the center. The problem is that very often the best reaction is a move on the same flank, which slows down the opponent substantially. And other times, just as frequently, it’s effective to attack on the opposite flank, because you’re faster, you win the race. Again the same conclusion is reached – it is the concrete analysis of the existing possibilities that leads to finding the appropriate strategy. You don’t find the correct move by starting from a rule, because in almost any position you can find different moves that satisfy different rules. Once you’ve determined which move works, you can triumphantly state that it’s rule X that’s highlighted here. From a didactic point of view, it is very tempting to take a position whose concrete best move or solution is already known to you, the coach, and pretend that you arrive at that solution by following the verbal protocol that is the theme of the lesson. But you would have arrived at a different move had you followed the verbal protocol of a different lesson. Today the student learns that in positions with an extra pawn it is good to trade pieces, and goes over nice clean examples where the extra pawn has been elegantly converted. Tomorrow the exact same student is criticized for trading pieces in his own pawn up game, because it lead to a drawn rook ending. The day after tomorrow the student trades instead of finding the idea of an attack on the king, where he had superior forces. And the third day he gets trashed because he tried to attack the king, took some risks and lost, instead of trading pieces and playing for two results. 🙂

General rules don’t tell us what move to play

Also related to general rules, there are many that contradict each other and as a result are absolutely useless from a practical point of view. There are examples where, in the same book, one page reads “don’t defend passively when you are worse, look for counterplay, even if it means investing material”, and just a few pages later “be patient, prolong resistance, don’t make things worse by reckless actions.” Obviously, both rules followed by game examples. It can even get funny – actual book – on page 120 we find “don’t stress about finding the best move; be pragmatic, just find a good move”, after which on page 124 we learn that “if you found a good move, look for an even better one!”.

There is no big plan

The books are full of examples where one side follows a certain plan from the beginning until a decisive advantage is obtained. In reality, this is extremely rare when players are close in strength. It could happen when Capablanca or Alekhine defeated someone much weaker. In a modern game it’s more common to have a number of small plans, and sometimes have to be changed along the way, because the opponent reacts to everything we are trying to do. The illusion, however, is maintained at the didactic level, even if we know today that many of those classic games often cited only describe what the author already knew. The annotations were produced with the power of hindsight.

Critical moments are not obvious during the game

There is a very widespread idea that in every game there would be 1-2-3 critical moments, where the player should spend a lot of time to find the right move. A game viewed from the outside, after it has been completed, appears to consist of long sequences of simple, natural moves, interrupted by critical moments when either white or black made a mistake or found an exceptional move that changed the balance of the game. But the way players perceive the battle, during the game, is the complete opposite. They feel the tension and weight of decisions at almost every move, with very few being seen as obvious, or simple. The proof is that mistakes can be made at any moment of the game! It’s easy to come back later and say – look, this is where you should have thought more. Most of the time it is difficult to determine the so-called critical moment while playing, it only becomes obvious later.

It is not always bad form

Most people have a complete lack of understanding of natural statistical distributions. It just doesn’t match their intuitions. Out of a large number of throws, a perfectly balanced die lands on each face with approximately the same frequency (1/6 of the total). But this does not mean that there are no series in which a number appears much less frequently or more frequently. It is perfectly possible that out of the first 60 rolls, the number 1 will not come up 10 times, but 4 times or 18 times. In the same way, two players with exactly the same rating and strength will have asymmetrical results in a match. It is possible that from the first 10 games one of them leads 7-3, without it being proof of the other guy’s lack of form. By playing more games, the score will even out. A 2200 player will have tournaments where the result corresponds to a 2000 level and others where it is similar to a 2400. This is completely natural.

It is not always about psychological factors

There is an exaggerated tendency to explain mistakes by psychological issues, instead of the real technical reason. Too often we hear explanations like “I was afraid of the opponent”, “I was obsessed with the clock ticking down”, “I was still thinking about the previous opportunities”, etc. instead of actual chess reasons (not enough familiarity with the idea behind the tactic, calculation too slow or not deep enough, bad selection of candidate moves, etc.). The main reason people lose games has little to do with psychology and feelings. Those negative emotions are the result of losing control over what’s happening on the board (and not the other way around).

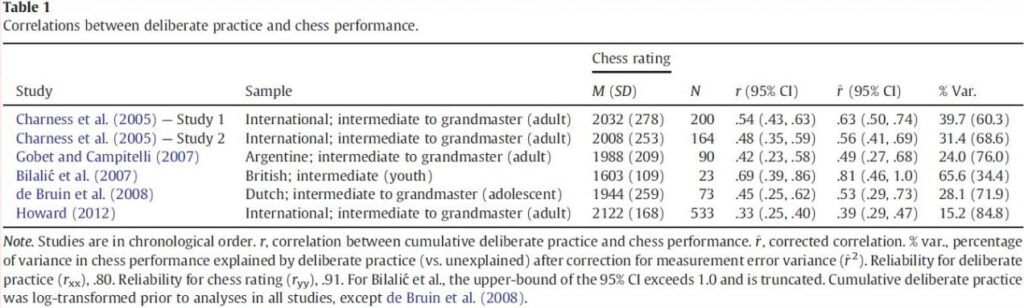

Hard work is not enough

The role of talent, which is genetically determined, is incomparably greater than most people realize. There are players who will never get past 2000, or 2300, or 2500, regardless of the amount of work and quality of instruction they receive. It’s a topic I have talked about at length on other occasions, I’ve even added an example to the blog. I’m glad Hendriks and others have reached the same conclusions.