My chess journey

How does the knight move?

My dad taught me the rules when I was 9. He had no formal chess training, but was strong enough to beat most amateur players. For the next 6 years, the only games I played were against him. And that didn’t happen often. Maybe once a month. Also, the games were not pretty. I would either get checkmated early (usually on f7/f2), or lose all of my pieces.

The second chess-related activity during those years was to watch 2 neighbours playing. They seemed to enjoy it a lot. It was a rivalry that lasted for years. On almost any non-rainy day, they could be found on the exact same bench, furiously moving pieces on the same ancient board. Never taking more than 5 seconds on a move. One of them was around 75 years old. The youngster around 60. With the power of hindsight I can say that the level of play was not great. The younger guy won many games by using sleight of hand techniques. For example, when both had pawns rushing to promotion, his pawn constantly jumped 2 squares ahead. He would always queen first, regardless of where the pawns started the race.

The third chess activity, the only one that I really enjoyed in fact, was to watch a weekly TV show called “Șah-mat în 15 minute”. Those of you with very high IQs will probably realize that it translates as “Checkmate in 15 minutes” and 15 minutes was the duration of each episode. The host was WGM Elisabeta Polihroniade, who did a lot to popularize chess among Romanians back then. The most interesting part was going through famous games of the past, such as Morphy’s brilliancies. I didn’t understand much as a total beginner, but I liked the stories and the final checkmating positions.

Hey, that’s a chess book!

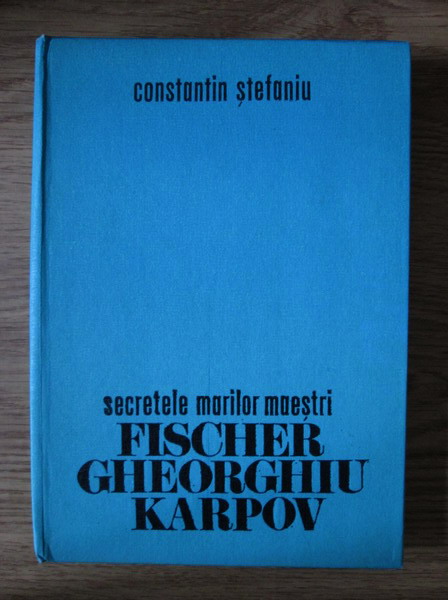

On the day I turned 15, something really special happened. My mom bought a book (it was one of the birthday gifts). The title was “Secretele marilor maeștri: Fischer, Gheorghiu, Karpov”.

If your intuition is good, you should guess that it means “Grandmaster secrets: Fischer, Gheorghiu, Karpov”. Gheorghiu was, of course, the best Romanian player at the time, at some point reaching top 10 in the world. Fischer and Karpov were also decent players, quite popular among chess aficionados. The book had hundreds of games played by these guys, many of them annotated. For some reason, I decided to actually go through the moves of the first game, playing them on my own chess board. The young generation will find it very hard to understand the process – it all had to be done manually, without screens, without clicking, and on a board without coordinates. That was a big problem. Today I could probably write a 200 page book about the f5 square, including games, tactics, strategies, plans and so on. But back then, I had to use my little fingers and sharp eyesight to determine what they meant by f5. And things didn’t always go according to plan. It took me around 3 hours to reach the end of a 50 move game. It wasn’t just that I didn’t understand the reason behind many of the moves, it was mainly because I kept running into illegal moves caused by misplacing a piece earlier.

100 games and a few weeks later I became quite competent at placing the pieces on the right squares, I could do an entire game in 2 minutes if I wanted. Shockingly, even the moves started to make sense. Maybe not all of them. I discovered amazing things. To list just some of them:

- It is not necessary to capture all of the opponent’s pieces in order to win a game

- In fact, sometimes these guys even lose material deliberately and the author would use strange words to justify it (attack, initiative, compensation, development, space, coordination)

- The move 1.e4 is not the only legal first move!

- Even when 1.e4 is being played, black is not forced to play 1… e5, and when they do, developing the queen to h5 is not popular at all

- There are very few games ending in checkmate, usually at some point one side hates their position so much that they just resign the game

- The early stage of the game is called the opening, and they have names and are easy to learn after seeing the same sequence over and over again

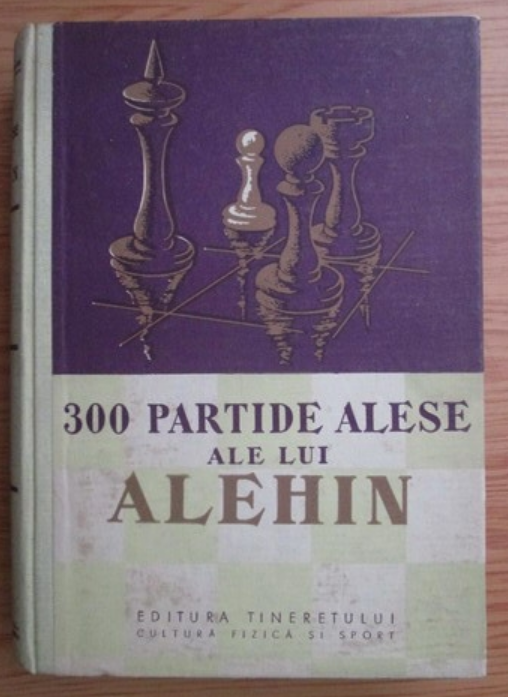

I loved studying these games so much, that I decided to buy another chess book. I chose the thickest I could find and I knew it had what I wanted, because it was right there in the title, something about 300 games played by a guy called Alekhine, supposedly a famous player of the past.

With Alekhine, it was love at first sight, there is no doubt about it. I liked his attacking style so much, that I finished the book in less then a month, and then I did it again. This time, using a technique I still advocate to this day, “guess the move”. Being the genius that I am, I handcrafted a cardboard device that would neatly cover the bottom part of the move list, and try to guess Alekhine’s moves. My guess rate kept creeping higher for months, reaching insane levels of around 70%. Probably it was also because I already knew some games by heart, but the truth is that I started to think like him. For many years to come, my style of play was heavily influenced by my first months of chess that I spent studying this book. The good part is that I developed a great sense for building an attacking position, playing on both flanks, setting up deep traps. The not so good part is that I didn’t enjoy playing dry positions or being forced to defend passively.

What you see on the left is a 15 year old nerd who spends 8 hours a day trying to guess moves played by some world champions. And he did that for 6 months. How is that possible? Wasn’t there anything more interesting to do? Short answer – there wasn’t. We’re talking about communist Romania in the early 80s. There is no internet. No mobile phones. Only one TV channel, black and white, 3 hours/day, most of it being an ode to president Ceaușescu, north-korean style.

But that ridiculous (according to modern standards) way of studying chess came with unexpected benefits. By studying huge collections of games, many of them annotated, I managed to get a wide understanding of very different openings, plans, structures, endgames and so on. Without playing a single tournament game, I felt that I already knew a lot. Today, after decades of teaching chess, I realize how lucky I was to start that way.

Today, a common scenario is to start working with a 10-14 year old, who already had another coach, sometimes for years. And I discover that he/she doesn’t know anything about typical ideas for white or black in an open Sicilian or a Ruy Lopez. Doesn’t know how an h file attack works against a fianchetto formation. Doesn’t know what we mean by Benoni or Gruenfeld. Has no idea how to play positions with a big dynamic advantage, down a pawn, has never played a gambit or studied such games. Why? Because the ex-coach only taught him/her 2-3 plans of the London system as white and another 3 for the Caro-Kann as black. And all the games he/she ever played or analyzed followed the same patterns, anything else is completely foreign.

I am not the weakest player in the world

The big day arrived. I discovered a local chess coach and club, it was some sort of scholastic chess program. I got there first in the middle of an endgame session. There were kids between 9 and 16 years of age, boys and girls. Some of them had already been playing chess for years. My heart was pounding, seeing the Coach himself, who was supposed to be something like a 1900 rated player (that felt like a chess god to me), and those young players who could probably beat me 10-0 in a match. They were staring intently at a chess board, with the next position on it:

It was a white to move and win type of puzzle. Every kid had a piece of paper in front, where they were supposed to write down the solution as soon as they find it and hand it over to the coach. I started to think about the position myself, and found the win in 1 minute or so. I didn’t say anything, I was new, didn’t even have the piece of paper like everybody else. I was just looking in disbelief at the others, not understanding why they were still thinking. After a few more minutes the coach said something like “so? … noone? …”. I gathered enough inner strength to say “I think I have it!” and then proceeded to show the solution.

The coach didn’t react the way I expected. He looked at me as if I had broken some rules. His remark was “You said you were a beginner!?”. Then he immediately asked me to play a training game against their star pupil, a bit younger than myself, a game that I managed to win.

When I finally played my first tournament games, I realized that I knew more chess than most of my opponents, some of which had been playing for many years. I was very surprised to see that some of them couldn’t tell what I meant by the classical King’s Indian pawn structure, or the Sozin Sicilian, the outside passer or the smothered mate. The excuse was always something like “oh, I don’t play that opening … I don’t like closed positions … I have my own style”.

That same year, when I played the national U16 junior final, I was the only player starting with a national rating below 1200. Most were around 1900. Some of them already had FIDE ratings, there was even a FIDE master playing. Around 100 participants. I finished second, same number of points as the winner, who had a better tie-break score (Sonneborn-Berger).

Can I get to 2000 in 2 years?

In the next 2 years (high-school years, or years 2-3 of my chess career), things started to change. I played a lot. I started to win games against players around the 2000-2200 level, and even won some games against national masters (2200+ level). I discovered strategy books, endgame books, but what I loved most was … solving puzzles. I started to get the Chess Informants to prepare my opening lines. For those too young to know, the Chess Informants (Šahovski Informator) were like ChessBase plus Chessable on paper. Very heavy paper I must say. There were 2 (later 3) volumes per year, covering all the important games and opening novelties of the last few months. When playing team tournaments, there was a specially designated team member carrying a bulging suitcase with the last 10 years of chess novelties. Being young and strong, the honor of making all that chess wisdom available to the rest of the team fell on me more than once.

I can still hear my mother’s voice in my head: “Your football matches are now once a month instead of almost daily like a year ago … you spent our seaside holiday with that stupid puzzle book of yours instead of swimming … why don’t you find a nice girl to go out with instead of staring at the chess board all day long?” I think she had a point there. But I did break the 2000 level, so it wasn’t in vain.

Decision time

Then, at the age of 17, I had to make a tough choice. To put things in perspective, I should mention that I was at the top of my class. From day 1 at school, at 6 years old, until graduating the medical school at the age of 25 – always the highest marks/grades/scores. I didn’t care much about grades and didn’t spend as much time as others learning/studying/doing homework, but I think I had an innate ability to grasp new concepts and learn with ease. My teachers knew that, and (unfortunately) my parents also knew it. They put it bluntly – “You’re very smart. You can become anything you want. How many rich chess players have you met? Start working on your future, prepare to become a doctor or a lawyer, you have time to play chess for fun when you get a real job”. I also met IM Mihai Ghindă, probably the best Romanian coach, the one and only ”GM Maker”, who after 2 hours of testing me and going through my games said something along the lines of ”You are very talented, you can be 2600 FIDE in a few years … but only if you forget about college and do this professionally”. I reached a point where heart said “study chess” and brain said “be a doctor”. Flipping a coin didn’t look like a good idea. I ended up making a deal with my parents. I was supposed to play an event in Poland in a month’s time. Strong U20 players from all over Europe. Finishing among the top 3 in that tournament meant I could do whatever I wanted, including the chess GM path. 4th or worse meant thousands of hours memorizing boring biology and chemistry texts. The third school subject was physics, but I was already quite good at that. Why all that? Because admission to the University of Medicine in communist Romania was very tough. Being a doctor was one of the very few things that was respected by the entire society and also paid well compared to other professions. It would typically be something like 100 available spots and 1500 well prepared candidates (including expensive private tutoring) fighting to get one of them.

So … what happened? There is only one way to describe it. I got played! 😒 Unbeknownst to me, my parents had already talked to some knowledgeable people working for the Romanian Chess Federation, and they guaranteed that I had no chance to finish among the top 3 players. My optimism generated by fast improvement was no match for the experience and playing strength of some of the players that showed up. I ended on a +1 score (5 wins, 4 losses, 4 draws), a decent result (even gained rating points), but nowhere close to top 3. That sealed the deal and I guess you know how I spent my year. Not studying or playing chess. To make matter worse, that was followed by another non-chess year – compulsory military service.

College years – tough, but the IM title is in sight

The college years were interesting. We got rid of communism. For the first time, I had a PC, and soon the first versions of ChessBase landed on it. It’s hard to describe the elation I felt when I discovered that it was possible to find opening positions and games played by various players by using a mouse, instead of spending hours searching through books. I tried to study and play whenever possible, but that had to be mostly during the summer breaks. It was not the kind of place and time where you could tell a university professor something like “hey buddy, sorry I can’t be here next week for the physiology of the heart lessons, I want to test my new Ruy Lopez repertoire instead”. Plus the exam sessions were tough. But even with so little time, I managed to gradually raise my level of play. I started as a freshman rated 2150 FIDE and 5 years later I was a confident young doctor and international master rated above 2400 FIDE, happy with my love life, professional future and hobby. Does the picture convey that feeling? 😊

What about GM? Life got in the way

The plan was clear in my mind.

- Choose a branch of medicine that suits me, definitely not surgical (didn’t want to spend my life in operating rooms). Something logical, interesting, such as Neurology.

- Any amount of learning, any exam necessary to get there – I can do that.

- Then find a nice cozy job, and outside Hospital hours keep working on chess.

- Take weeks off to play tournaments, maybe aim for the GM title.

The first part went according to plan. I got stuck somewhere between 3 and 4. Started to teach Neurology to med students, as a professor assistant. More exams. Long duty hours. Started to work on my PhD. Taking weeks off whenever I wanted? LOL. Not even close to that. I met my future wife. Guess what, she was a chess player as well (WIM), and we met during a chess event. Many things changed, especially after we had our first child.

I kept playing for a number of years, on and off. I even came close to scoring the GM norm twice, but it was very clear to me that with my schedule and the non-professional approach I had, it would be impossible to get the title. Of course, I won tournaments, I won games against GMs, I played many beautiful games, but the consistency was lacking (as expected). I stopped playing in 2007, then played a few more events in 2013-2018, simply because I wanted to travel with my son Victor, who became a FIDE master himself.

Teaching chess from home? Amazing stuff!

In the late 90s I also discovered that I enjoyed teaching chess. I worked with some talented local juniors, and not without success. For example, Szabo Gergely later became a GM and a very successful coach himself. I would argue that by coaching a future GM coach, who has students who have become titled players, I am entitled to the Final Boss title in coaching. Or I’m just very old, not sure.

Since I’ve reached the coaching part, I should definitely talk about the defining moment. It happened in 1999. Online chess was in its infancy. The best place to play online (by far) was ICC = Internet Chess Club = chessclub.com. At its peak, ICC had tens of thousands of subscribing members and pretty much any titled player with an internet connection was there. I was lucky enough to play blitz games against superstars like Morozevich, Grischuk, Short, or a very young Hikaru Nakamura. Please don’t ask about the score.

It was a nice Saturday night. September 1999. I couldn’t fall asleep. I didn’t know why. Today I know, thanks to Ismo.

Since counting sheep didn’t help, I thought it was a good idea to play some games online. I’m sure I am the only person in the world playing chess instead of sleeping. Normally, my seeks had rating limits (e.g. opponent had to be above 2300), but I forgot to set those limits, and a random 1900 guy accepted the challenge. We played 2 games, I won as expected, and then he had some questions about the games. I started to type my answers (voice communication came much later) – chess stuff, that felt quite basic to me, but the guy seemed to be very happy. He told me that I had exactly what it took to become a vendor on ICC. I didn’t even know what he meant by that. He told me that as a titled player, I could apply to become a chess coach on ICC, and get paid for that. After quickly going through some help files, I realized that he was telling the truth. I also started to notice that some GMs were advertising their vendor services (technically it was called sshouting). I clearly remember people like GM Pablo Zarnicki (garompon) or GM Sergey Volkov (volkov) doing that. By the way, exactly one year later I managed to defeat Volkov in a very interesting otb game (let’s call it the battle of vendors). 😉

I did apply to become a vendor, and was accepted. It felt a bit too good to be true. Just think about it. I can teach people who are not from my city. I don’t have to travel. I can keep my normal day job at the Hospital and in the evening help a guy from Delaware understand the Carlsbad structure? And then even get paid for it? Who’s going to do that?

It quickly transpired that many people were willing to do it. My results were quite good, people seems to like my style, many said that they finally saw rating improvements after years of being stuck. I didn’t have to do the sshouting thing, the students were doing the advertising by playing well and talking to their opponents after the game. It gradually dawned on me that this was “the thing” for me. I didn’t have the time, the energy or the right age to become a great chess player. But I still loved chess. I had a gift for teaching, or at least that is what my med students were saying. Both parents are teachers, could it be in the genes?! I’ve always been punctual, well organized, perfect health, decent English (learned on my own, just like chess).

So … here we are. The adventure is not over!